DEMO SCORM

znasz podstawy HTML?

— możesz produkować kursy takie jak ten!

nigdy nie było tak ŁATWO tworzyć SCORMy

DEMO SCORM

znasz podstawy HTML?

— możesz produkować kursy takie jak ten!

nigdy nie było tak ŁATWO tworzyć SCORMy

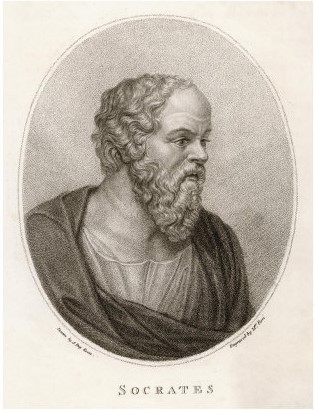

In the term critical thinking, the word critical, (Grk. κριτικός = kritikos = "critic") derives from the word critic and implies a critique; it identifies the intellectual capacity and the means "of judging", "of judgement", "for judging", and of being "able to discern". The intellectual roots of critical thinking are as ancient as its etymology, traceable, ultimately, to the critical reasoning of the Presocractic philosophers, as well as the teaching practice and vision of Socrates 2,500 years ago who discovered by a method of probing questioning that people could not rationally justify their confident claims to knowledge.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the exact term “critical thinking” first appeared in 1815, in the British literary journal The Critical Review, referring to critical analysis in the literary context. The meaning of "critical thinking" gradually evolved and expanded to mean a desirable general thinking skill by the end of the 19th century and early 20th century.

Critical thinking is a core academic skill that enables students to analyze information, evaluate arguments, and make reasoned judgments. It is not about criticism, but about disciplined reasoning.

Critical Thinking — the ability to actively and skillfully conceptualize, apply, analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information to guide belief and action.

In higher education, critical thinking is expected across disciplines: humanities, sciences, engineering, medicine, and social sciences. It supports academic writing, research, problem-solving, and ethical decision-making.

Universities emphasize critical thinking because students constantly face:

Critical thinking helps separate evidence from opinion, recognize assumptions, and assess credibility.

Critical thinking is embedded in curricula through essays, research projects, laboratory reports, and discussions.

Outside academia, it supports informed citizenship, media literacy, and professional decision-making.

Critical thinking is not:

Critical thinking consists of interconnected cognitive skills. These skills work together rather than in isolation.

Drawing logical conclusions from available evidence, even when information is incomplete.

Explaining the meaning of information, data, or events in context.

Beyond individual skills, critical thinking functions as an integrated cognitive process. Analysis without evaluation leads to fragmented understanding, while evaluation without interpretation risks superficial judgment. In academic contexts, students are expected to coordinate these skills simultaneously: interpreting data, analyzing arguments, and evaluating conclusions within disciplinary standards. This integration distinguishes critical thinking from isolated study techniques.

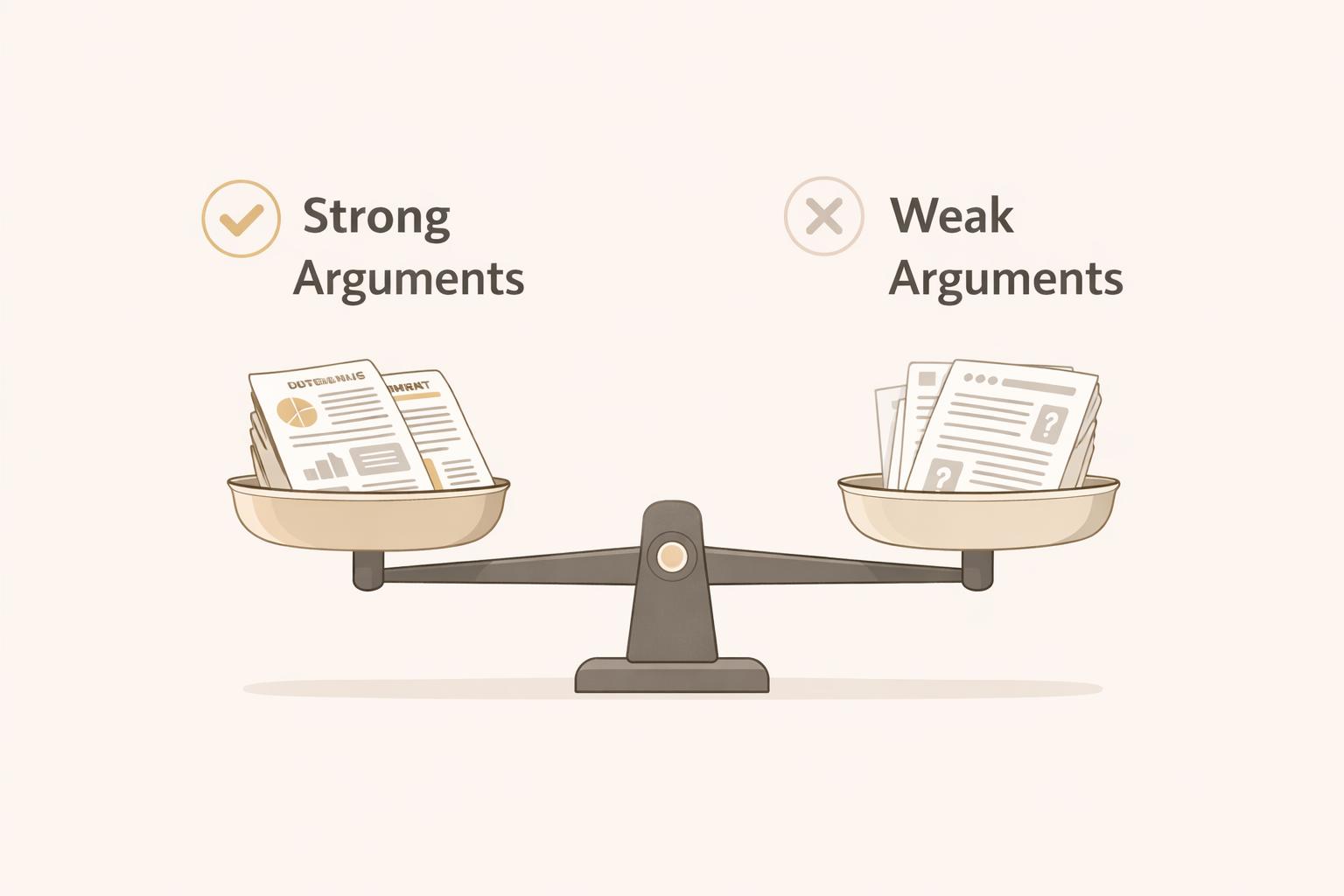

Analysis — breaking complex information into parts to understand structure and relationships.

VS

Evaluation — assessing the credibility, relevance, and strength of evidence or arguments.

Importantly, critical thinking is context-dependent. The way evidence is evaluated in physics differs from historical analysis or ethical reasoning in philosophy. However, the underlying cognitive structure remains consistent: clarify the problem, examine assumptions, assess evidence, and justify conclusions. Recognizing this transferability allows students to apply critical thinking skills across courses, research tasks, and real-world problems.

| Skill | Description |

|---|---|

| Analysis | Identifying arguments, claims, and evidence |

| Interpretation | Understanding meaning and context |

| Inference | Drawing logical conclusions |

| Evaluation | Judging credibility and relevance |

| Explanation | Clearly justifying reasoning |

| Self-regulation | Reflecting on one’s own thinking |

Academic research requires systematic and critical engagement with sources. Students must move beyond summarizing texts toward evaluating them.

Scholarly Source — a publication written by experts and reviewed by peers before publication.

Critical thinking in research involves:

Reading academic research critically means going beyond surface comprehension. A research paper should be approached as a structured argument rather than a collection of facts. Students must identify the research question, understand why it matters within the discipline, and analyze how the methodology supports the conclusions.

Evaluating academic sources requires systematic judgment of credibility and relevance. This includes examining the author’s expertise, the publication venue, and whether the work has undergone peer review. Students should assess how recent the source is, how well it is cited, and whether the evidence aligns with accepted research standards. Critical thinkers also consider potential bias, funding sources, and the broader academic context in which the work appears, rather than relying solely on authority or reputation.

Avoiding plagiarism is not only a technical skill but a component of critical thinking. It requires understanding ideas deeply enough to restate them accurately in one’s own words and to integrate them into an original argument. Proper citation acknowledges intellectual ownership and allows readers to verify sources. More importantly, ethical academic writing depends on independent interpretation, synthesis of multiple perspectives, and transparent distinction between personal reasoning and referenced material.

Arguments are central to academic discourse. Critical thinkers distinguish between valid reasoning and logical fallacies.

Argument — a set of statements where one (the conclusion) is supported by others (premises).

Logical Fallacy — an error in reasoning that weakens an argument.

| Fallacy | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Ad hominem | Attacking the person, not the argument |

| Straw man | Misrepresenting an opponent’s claim |

| False dilemma | Presenting only two options |

| Appeal to authority | Using authority without evidence |

| Hasty generalization | Drawing conclusions from limited data |

| Circular reasoning | Conclusion repeats the premise |

Academic writing reflects the quality of thinking behind it. Clear structure and justified claims are essential.

Thesis Statement — a clear, concise claim that guides the entire academic text.

Strong academic writing:

Data, quotations, and references must support claims.

Critical thinkers revise to improve clarity and logic.

Critical thinking includes awareness of personal and cultural bias.

Cognitive Bias — systematic patterns of deviation from rational judgment.

Recognizing bias is essential in:

Ethical reasoning ensures responsible academic and professional conduct.

A cognitive bias is a systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment.

The tendency to favor information that confirms existing beliefs.

Bias does not eliminate critical thinking, but unrecognized bias significantly weakens it. Academic judgment is shaped by prior knowledge, cultural background, disciplinary traditions, and personal experience. Critical thinkers therefore practice deliberate reflection: they question why certain explanations feel convincing and whether alternative interpretations have been fairly considered. By actively seeking disconfirming evidence and engaging with opposing viewpoints, students reduce the influence of unconscious bias and strengthen the reliability, transparency, and ethical quality of their academic reasoning.

Ten SCORM przetestowany na większości dostępnych urządzeń i przeglądarek. Ta sama treść wizualizuje się komfortowo wszędzie, od telewizora na całą ścianę po najmniejszy telefon, od Firefoxa po Safari. Prawdziwa realizacja hasła „Ucz się gdzie chcesz!”.

Interfejs nawigacyjny dostosowany zarówno do obsługi dotykowej (gesty swipe), jak i do pracy z klawiaturą. Klawisz HOME otwiera ekran powitalny, klawisz END — ekran podsumowania, klawisze ze strzałkami odpowiednie — góra, dół, poprzednia strona, następna.

Warstwa techniczna zajmuje zaledwie około 30 KB — pozostałą część stanowi treść dydaktyczna. SCORM tego kursu zajmuje 1 MB. W środowiskach akademickich, gdzie z kursów jednocześnie korzystają setki lub tysiące studentów, taka lekkość przekłada się na szybkie uruchamianie i mniejsze obciążenie infrastruktury.

Wbudowany emulator umożliwia obejrzanie i edytowanie kursu bezpośrednio w przeglądarce lokalnie, bez instalacji Moodla i narzędzi autorskich.

Czysty, natywny HTML, JavaScript i CSS, bez użycia zbędnych bibliotek czy frameworków. Minimalistyczny, dopieszczony kod pod maską zapewnia wysoką wydajność oraz pełną kontrolę nad każdym elementem kursu.

Modularna architektura umożliwia szybkie i efektywne dostosowanie wyglądu, interaktywności oraz logiki działania do indywidualnych wymagań projektu lub instytucji.

Zaliczenie strony zależy od czasu spędzonego na przeczytanie contentu odniesione na ilość contentu na stronie. Czas zaliczenia można elastycznie dostosować do prędkości czytania grupy docelowej, np. dzieci, studenty akademickie lub uczestniki szkoleń biznesowych.

Zgodność z WCAG 2.1 AA, wielojęzyczność, tryb jasny/ciemny oraz asystent AI.